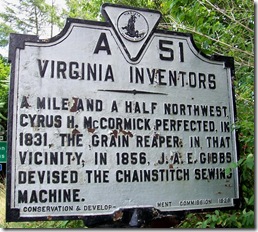

Rockbridge County, VA

Rockbridge County, VA Marker No. A-51

Marker Text: A mile and a half northwest, Cyrus H. McCormick perfected, in 1831, the grain reaper. In that vicinity, in 1856, J. A. E. Gibbs devised the chainstitch sewing machine.

Location: On U.S. Route 11 (Lee Jackson Highway) at the intersection with Route 606 (Raphine Road) in Steeles Tavern near Rockbridge/Augusta County line. Erected by the Conservation & Development Commission in 1929.

Today's marker located near the county line of Rockbridge/Augusta is an older one with the customary shorter text used in the early markers. The marker makes simply references to two inventors who lived in the area, Cyrus McCormick and J.A.E. Gibbs.

If you remember your high school history you probably remember Cyrus McCormick and his historically significant invention of the grain reaper. McCormick joined with his father who earlier attempted to invent a machine to help in the harvest of wheat and his father's interest came from the crops grown at the family farm. The Shenandoah Valley of Virginia was one of the top grain-producing regions in the country from the last part of the 18th century to early in the 20th century. Growing grain, particularly wheat, rye and/or oats, required intensive labor. Harvest involved backbreaking stooping and bending with tools, such as, sickles, scythes or grain cradles.

Text: Cyrus H. McCormick, inventor of the reaper was born on this farm Feb. 15, 1809. Here he completed the first practical reaper in 1831. Erected by V.P.I. Student Branch American Society of Agricultural Engineers 1928

Text: Cyrus H. McCormick, inventor of the reaper was born on this farm Feb. 15, 1809. Here he completed the first practical reaper in 1831. Erected by V.P.I. Student Branch American Society of Agricultural Engineers 1928

Robert McCormick’s son, Cyrus, grew up watching his father tinker with machinery in the farm’s blacksmith and carpentry shops and in the mill. Cyrus was born on the farm Feb. 16, 1809. By the time he was 22, he learned enough from his father that he invented and patented a hillside plow. Two years later, he invented another plow.

Then Cyrus decided to tackle the reaper project his father had abandoned years before. His father attempted to discourage his efforts believing that he would ultimately fail, but Cyrus knew how important such a machine could be to farmers. Finally during the summer of 1831, the machine was ready to be tested. Cyrus McCormick successfully cut six acres of oats in a field owned by John Steele. McCormick received his first reaper patent in 1834, but the machine was not an immediate success. As often is the case with successful inventions they are as much about wise marketing, timing and location.

McCormick did not initially invest all his time in reaper production. He remained on the family farm and hand-built custom machines a few at a time. After some promising success selling his reaper in Virginia, McCormick soon realized that the Midwest was the place to make money in grain, and he moved his manufacturing production, first to Cincinnati in 1845 and then to Chicago in 1847. During those years, he also received additional patents for improvements he made to his reaper.

In 1847, 700 reapers were built after he was established a factory in Chicago. That number more than doubled to 1,500 the next year. From 1850 to 1858, his manufacturing company built and sold more than 70,000 reapers. The reaper made Cyrus McCormick a wealthy man.

In 1847, 700 reapers were built after he was established a factory in Chicago. That number more than doubled to 1,500 the next year. From 1850 to 1858, his manufacturing company built and sold more than 70,000 reapers. The reaper made Cyrus McCormick a wealthy man.

Despite the fact that he earned his fortune out west, he remembered his Augusta/Rockbridge County roots. McCormick and his family donated generously to the Staunton public library, Old Providence Presbyterian Church and Washington and Lee University were among the recipients. He also donated $100,000 to the Presbyterian Theological Seminary of the Northwest in Chicago, which after his death was renamed, McCormick Theological Seminary and is a seminary related to the Presbyterian Church, (U.S.A.), which so happens to be the seminary I attended.

On May 13, 1884, McCormick died at his home in Chicago. He died a wealthy and prominent businessman, whose invention had changed the scene of agriculture around the world. A two-acre memorial plot at the Shenandoah Valley Agricultural Research and Extension Center located west on Route 606 from this marker pays tribute to Cyrus McCormick and the McCormick family. The memorial area is designated a National Historic Landmark and Virginia Wayside site.

Sewing Machine Inventor

The marker makes reference to sewing machine inventor James Edward Allen Gibbs who was born in northern Rockbridge County on Aug. 1, 1829.

The marker makes reference to sewing machine inventor James Edward Allen Gibbs who was born in northern Rockbridge County on Aug. 1, 1829.

After growing up in the area, he moved to West Virginia where he employed his mechanical skills at a variety of trades including milling and surveying. In the 1850s, after seeing a crude woodcut of a sewing machine, he decided he could invent one of his own and went into the sewing machine business. Before the Civil War, Gibbs hooked up with the father and son duo of James and Charles Willcox. The father, James was a financier and the Charles, his son was an inventor like Gibbs. Together as Willcox and Gibbs, they began manufacturing Gibbs’ invention in 1858 and opened a New York city office to market their machines in 1859.

When the Civil War broke out Gibbs remained loyal to the South and brought his family back to Rockbridge County where he remained the rest of his life. Gibbs enjoyed some success with his sewing machine before the Civil War, but the conflict prevented his involvement in the ongoing operation. At the war’s conclusion he traveled to New York to see if anything was left of his company and discovered that he was a rich man.

The Willcox's had protected Gibbs’ interests in the company and he discovered he was a much wealthier man. As a result, Gibbs was able to take up where he left off before the war. Having decided that he would remain in Rockbridge and turn his attention to marketing the Willcox and Gibbs machine in the South.

The Willcox and Gibbs machines used a chain stitch meaning that just one thread was used rather than the two threads seen in most machines today. Willcox and Gibbs prided themselves on having a machine that was affordable for the average household. In the 1870s one of their machines with an iron stand cost $55, while one with a mahogany half case was still a reasonable at $67.

As long as he lived, Gibbs continued to take an active role in the local community. In 1883, when the Baltimore and Ohio railroad came through, he allowed the line to be run across his land. He also donated land for a station with the stipulation that it be called Raphine. Raphine came directly from an old Greek word which means "to stitch." Through his generosity to the railroad, Raphine also became the name for the hamlet through which the railroad passed.

Gibbs died in 1902 and the railroad no longer operates, but the name of Raphine remains as a testament to a man and his sewing machine.

No comments:

Post a Comment